Crude Reality: Crippling the Russian Bear

- Discuss Diglett

- Apr 30, 2025

- 12 min read

This article is co-authored by Luo Xuhong and Prathit Maran.

In a rare display of unity, major Western governments have implemented coordinated sanctions against thousands of Russian and Russian-linked individuals and firms since the full scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 with the main objective of hindering Moscow’s ability to finance its war machine. The majority of sanctions have targeted the energy sector. As the war marks a deadly 3rd anniversary, how has Russia managed to circumvent such extensive sanctions to sustain itself on the battlefield?

September 2022 saw the imposition of a price cap by the G7 nations together with the EU and Australia on Russian oil and petroleum products. More specifically, crude was capped at US$60/barrel, high-value (premium-to-crude) products e.g gasoline and diesel were capped at US$100 while low-value (discount-to-crude) products e.g naphtha were capped at US$45. Sanctions apply to those who provide protection and indemnity (P&I) insurance to ships carrying oil products that violate the price cap.

Underscoring Russia’s reliance on energy exports, revenue from fossil fuels (oil and natural gas) exports accounts for around one-third of Russia’s federal budget. Naturally, the G7+ oil price cap is seen as the most direct solution to hobble Russia’s capacity to finance its war machine while minimising disruptions to the global energy market.

However, the policy design of the price cap has unfortunately limited its effectiveness. Faced with the restrictions on oil revenue, Russia has swiftly amassed a so-called ‘shadow fleet’ of oil tankers that have no ties to any G7+ nation (and hence need not abide by any price ceiling).

A tactic first used in other sanctioned nations including Iran and Venezuela, Russia has amassed a fleet of aging, underinsured (or entirely uninsured) tankers to side-step the price cap and export its oil abroad at close to market prices. These vessels typically operate with obscure ownership and commonly manipulate AIS transponder data to obfuscate their locations from shipping authorities. Recent data suggests that more than 90% of Russian crude oil exports are now transported via its shadow fleet.

The price cap was followed up by the ban of all Russian seaborne oil imports (crude and its products) imposed by the EU and G7. Interestingly, this did not have a significant impact on Russian oil exports in terms of quantity (barrels per day). In fact, exports have been creeping up to pre-war figures in just a year into the “special operation”. In April 2023 Russia was exporting 8.3 million barrels per day up from about 7.7 million a year ago.

Notably, 3 member states Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic that were energy-dependent on Moscow were granted exemptions from the ban. Notably, the Czech Republic has ended all imports of Russian oil through investment in infrastructure to import oil from the west. The RePowerEU scheme obliges member states to cease all imports of Russian oil by 2027, however we do not think that this will significantly reshape Russia's export market landscape as the 2 remaining nations import relatively small amounts of Russian oil.

Russian oil firms have also faced a number of sanctions (e.g. EO 14066) that targeted the provision of financial services. They are also subject to restrictions on Western exports of certain oil production equipment/technologies. EO 14024 further extends this by permitting the US government, at their discretion, to impose secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that provide “significant transactions” to such firms. Secondary sanctions risk has led to major suppliers cutting business ties with Russian firms entirely.

While a reduction in the export of oil production equipment/ technologies to Russia is unlikely to have a major impact in the short term, it can cause worries for the future. If Russia is not able to invest more in the development of their own equipment or able to source sufficient high quality alternatives from countries such as China they could have a hard time replacing worn equipment and utilising new sources of oil. This will lead to a decline in their production capabilities.

We have already seen some instances of this happening. The Vostok Oil project in the Arctic has been delayed to 2026 due to sanctions hindering Russia's ability to obtain sufficient numbers of ice-capable oil tankers. Orders have been placed with Russia's Zvezda shipyard, however progress has been slow.

Moscow's exclusion from western capital markets has had a more profound impact in the short term. Projects have been delayed or canceled. Russian oil firms had to start borrowing from domestic banks with very high interest rates due to inflation. For instance, in early 2024 the interest of the average adjustable rate corporate loan was 16.8% p.a., significantly higher than what firms had been previously paying. Some institutions have also managed to obtain financing from friendlier nations such as China, however those are normally on highly unfavourable terms.

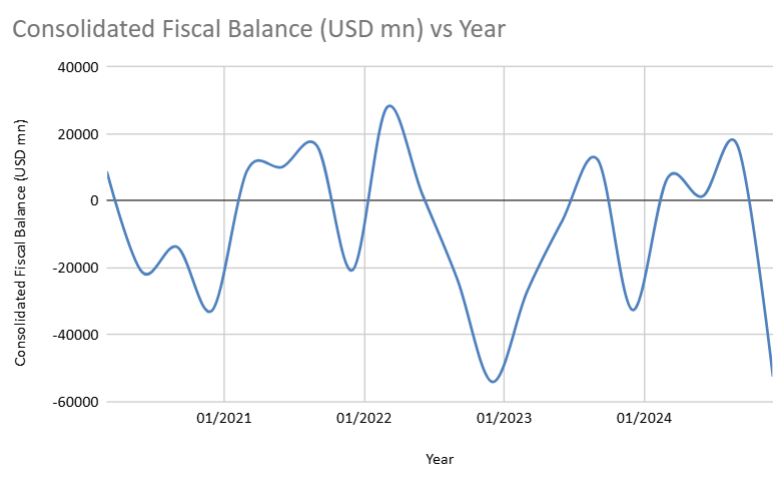

Russia's Fiscal Balance

The implementation of sanctions has taken a severe toll on Russian government oil revenues. With energy exports forming one of the main components for Moscow’s fiscal revenue, this has emerged as a major strain on Russia's fiscal balance.

Combined with falling revenues from other sectors and increased defense expenditure, the Russian government has to run at a deficit. This has forced Moscow to bridge the gaping hole by drawing down on the National Wealth Fund - it is valued at 140 billion USD as of March 2025, down from approximately 210 billion USD back in June 2022.

The fall in export revenue has also contributed to the weakening of the ruble. This is in turn linked to widespread inflation in Russia - by June 2022 the ruble had fallen more than 50% to 52 rubles per USD, even though it has recovered somewhat since then.

We can argue that the deficit has hindered the war financing effort to some extent. The added financial strain may have led the government to be more conservative with spending (outside of the defence sector). The falling rouble also directly translates into an increase in the cost of imported war-related equipment.

No Limits Friendship?

Mere weeks before Putin started the largest armed conflict Europe had seen since World War 2, he visited the Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing and declared their “no limits” partnership in a carefully choreographed moment. Indeed, in the immediate months following the war, the Chinese have stepped up efforts to help Moscow bypass the punitive sanctions imposed by the West.

Packages of financial sanctions have constrained the Russian state’s ability to collect energy revenue even when willing buyers are found. The European Union has moved swiftly (pun intended) to disconnect 8 Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system (used by thousands of financial institutions worldwide to process international payments). Gazprombank, the last major Russian bank used to facilitate energy-related transactions, was also targeted in a round of US sanctions late last year.

4 major Chinese banks have increased their investments in Russia by almost 5x over the initial 14 months of the war. However, this trend has seen a slowdown in the latter months of 2024, with multiple reports suggesting that US threats of secondary sanctions on non-compliant Chinese banks have sent jitters across the sector, delaying payments of billions of yuan.

In response, Russian firms have turned to potential workaround solutions involving the use of multiple smaller regional intermediaries that would slip through sanction dragnets. Yet, even though many of these regional banks may be more willing to process payments to sanctioned entities, doing so would likely expose their major Chinese banking partners (whom they have correspondent banking relationships with) to the same secondary sanctions risk as well. In the meantime, continued uncertainties have led to commissions on payments escalating to nearly 12% this month.

That being said, even extensive financial sanctions are far from forcing Moscow markets to grind to a halt. The Chinese yuan has effectively replaced both the US dollar and euro in forex trades on the Moscow Exchange as the default currency (that is used in more than 99% of all transactions).

Naturally, the “no-limits” partnership also extends to the energy sector. As Europe weaned itself off Russian gas (Russia accounted for 11% of total EU imports in 2024, as compared to 41% in 2021), the Kremlin has looked to the East for new markets to fill the void as sanctions bite. For instance, Moscow has anticipated the backlash by signing a 30-year agreement to supply natural gas to China just before the war’s outbreak. The contract includes the commissioning of Power of Siberia 2, a pipeline that is expected to export an additional 50 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas annually to the densely populated region of Northeastern China.

As a monopsonist however, China has had the upper hand in negotiations with Russia. Beijing is known for driving a hard bargain, dictating its preferred terms in energy agreements. While China is keen on reducing its consumption of coal, she is less willing to replace this with growing reliance on imported energy resources and has indicated a preference for increasing domestic energy production instead. In fact, PoS-2 has been mired in delays over unresolved disputes concerning the price of gas and cost-sharing for construction costs. If Moscow does not agree, China can always turn to Central Asia rivals Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to meet its energy needs.

"Potentially 150 billion cubic metres of production capacity stranded for the foreseeable future" ~ International Institute for Strategic Studies

Even with the new Chinese gas contracts, Moscow remains unable to redeploy its production capacity in full. Previous sanctions that exclusively target LNG facilities such Arctic LNG 2 have also slowed its commissioning (it is expected to start operations in mid-2025). It remains to be seen if China will be willing to risk the threat of secondary sanctions and purchase LNG supplies directly from the sanctioned plant. In fact, Chinese firm Zhoushan Wison Offshore and Marine found itself in the crosshairs of US sanctions for illegally supplying a power plant to the LNG project.

An Euro-Atlantic Divergence

As the Russian-Ukraine War enters its 3rd year, the second Trump administration’s Russia strategy has elicited ripples of concern among multiple European capitals. The days of unparalleled coordination among the US, EU and UK to draft and implement sanctions are coming to an end. Since entering office, Trump has spearheaded ceasefire negotiations directly with the Kremlin, leaving out traditional European allies from the talks. In the starkest sign of a growing transatlantic rift, the US has even voted against a UN General Assembly resolution condemning Moscow’s war.

At the same time, Trump has also dangled the possibility of lifting certain sanctions (March 2025) should a potential ceasefire deal be reached while appearing to soften his stance on Russia by disbanding a taskforce that was previously tasked with enforcing sanctions on Russian oligarchs. More recently, Trump has returned to his classic carrot-and-stick approach and lobbed threats of even tighter sanctions- one such proposal involves a 50% tariff on all Russian oil exports - as progress on the talks slowed. Evidently, Trump sees sanctions not as a policy but as a form of leverage in his attempts to strike a deal.

This is where the Europeans beg to differ. Brussels has insisted that Trump’s proposal to recognise occupied Ukraine territory as part of Russia is simply not acceptable. Unsurprisingly, the EU has preconditioned sanctions relief upon a full withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine territory. The bloc has also rebuffed demands to reconnect Russian banks to the SWIFT network (based in Belgium and technically outside of Trump’s jurisdiction).

Yet, Brussels is also cognisant of Washington’s economic might despite the growing divergence. Uniquely, the enforcement or renewal of any sanctions requires the approval of all 27 EU member states. Energy-dependent Hungary has repeatedly threatened to scuttle sanction efforts as recently as January this year, though a phone call from the Secretary of State Rubio convinced Budapest to eventually back down. However, the same pressure (that can extend to tariffs as well) from Washington can easily go the other way: it’s certainly not unimaginable for some EU nations to capitulate over Trump’s demands to ease sanctions.

The most extensive sanctions regime ever imposed by the West has undoubtedly slowed Putin’s war machine. Rosy economic figures mask the harsh realities for the average Russian citizen - from soaring costs of daily staples to dwindling purchasing power of the rouble. At the time of this article’s publication, Russia is in its largest conscription drive yet as Putin seeks to replace depleted ranks of the Armed Forces. Moscow’s maneuvers have also driven home the reality that sanctions are far from foolproof. After all, sanctions are only as effective as their weakest link, be it an oil trader in Dubai or a Beijing-based state-owned corporation.

References

Asia Financial. (2025, April 23). “Underground” Banking System Set up For China-Russia Trade. https://www.asiafinancial.com/underground-banking-system-set-up-for-china-russia-trade

Babina, T., Hilgenstock, B., Itskhoki, O., Mironov, M., & Ribakova, E. (2023). Assessing the Impact of International Sanctions on Russian Oil Exports. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4366337

BOFIT. (2025). Companies in Russia rely largely on domestic banks for financing. BOFIT. https://www.bofit.fi/en/monitoring/weekly/2024/vw202423_1/

Construction of “Power of Siberia 2” delayed. (2024, January 30). Table.Media. https://table.media/en/china/news/construction-of-power-of-siberia-2-delayed/

Edwards, R., & Bozorgmehr Sharafedin. (2022, May 5). Explainer: Why the EU may find it tough to squeeze out Russian oil. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/why-eu-may-find-it-tough-squeeze-out-russian-oil-2022-05-04/

European Commission. (2024, February 24). Sanctions on energy. European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-solidarity-ukraine/eu-sanctions-against-russia-following-invasion-ukraine/sanctions-energy_en

European Council. (2024). Timeline - EU sanctions against Russia. Consilium. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-russia/timeline-sanctions-against-russia/

Federal Register :: Request Access. (n.d.). Unblock.federalregister.gov. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/03/10/2022-05232/prohibiting-certain-imports-and-new-investments-with-respect-to-continued-russian-federation-efforts

Gavin, G., Vinocur, N., Verhelst, K., & Jack, V. (2025, January 27). Hungary backs down in EU Russia sanctions standoff. POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-backs-down-in-eu-russia-sanctions-standoff/

Goudsward, A. (2025, February 6). Trump administration disbands task force targeting Russian oligarchs. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-administration-disbands-task-force-targeting-russian-oligarchs-2025-02-06/

Hawser, A. (2024, July 8). Smaller Chinese banks at risk from US secondary sanctions on Russia, warn experts. The Banker. https://www.thebanker.com/content/311c4e37-5396-5dce-8381-294425744db1

Hirtenstein, A., & Tan, F. (2025, February 13). Insight: Russia braces for oil output cuts as sanctions and drones hit. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-braces-oil-output-cuts-sanctions-drones-hit-2025-02-12/

Hockenos, P. (2025, January 3). After Years of War, Europe Is Still Dependent on Russia’s Energy. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/01/03/europe-russia-ukraine-war-energy-imports-oil-gas-pipeline/

Humpert, M. (2024, December 12). Russia’s Rosneft Delays Arctic Mega Oil Project Due to Sanctions, Shortage of Oil Tankers. GCaptain. https://gcaptain.com/russias-rosneft-delays-arctic-mega-oil-project-due-to-sanctions-shortage-of-oil-tankers/

Humpert, M. (2025, April 21). China Looking to Buy More Russian Arctic LNG as EU Aims to Announce Plans in May to Phase Out Imports. High North News. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/china-looking-buy-more-russian-arctic-lng-eu-aims-announce-plans-may-phase-out-imports

Joe Biden bans Russian oil imports in “powerful blow to Putin’s war machine.” (2022, March 8). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/mar/08/russian-oil-imports-ban-us-joe-biden

Kazakhstan Strengthens Gas Exports to China in 2025. (2025, February 13). Energynews; Energynews. https://energynews.pro/en/kazakhstan-strengthens-gas-exports-to-china-in-2025/

Landale, J. (2025, February 25). US sides with Russia in UN resolutions on invasion of Ukraine. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c7435pnle0go

Liboreiro, J. (2025, April 23). Brussels rejects Russian recognition of Crimea and sanctions relief. Euronews.com. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/04/23/brussels-rejects-russian-recognition-of-crimea-and-sanctions-relief-included-in-leaked-us-

Lukoil Volgograd Refinery. (2021). NS Energy. https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/lukoil-volgograd-refinery/

Lyngaas, R. (2023, December 14). Sanctions and Russia’s War: Limiting Putin’s Capabilities. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/sanctions-and-russias-war-limiting-putins-capabilities

Moller-Nielsen, T. (2025, March 28). Europe’s unsanctionable predicament. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/europes-unsanctionable-predicament/

Nie, S., & Downs, E. (2024, October 2). Rising Production, Consumption Show China is Gaining Ground in Its Natural Gas Goals. Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University SIPA. https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/rising-production-consumption-show-china-is-gaining-ground-in-its-natural-gas-goals/

Office of Foreign Assets Control. (n.d.). OFAC. https://ofac.treasury.gov/faqs/topic/6626

Office of Foreign Assets Control. (2022). Office of Foreign Assets Control | U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://ofac.treasury.gov/faqs/1014

PillarFour Capital Partners. (2022, June 30). Q2 2022 Research Theme: The Impact Of Western Sanctions On The Russian Oil Industry. PillarFourCapital. https://www.pillarfourcapital.com/post/q2-2022-research-theme-the-impact-of-western-sanctions-on-the-russian-oil-industry

Prohibiting Certain Imports and New Investments With Respect to Continued Russian Federation Efforts To Undermine the Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity of Ukraine. (2022, March 10). Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/03/10/2022-05232/prohibiting-certain-imp

Reuters. (2023, March 15). Factbox: How the EU ban on Russian oil imports affects oil flows. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/how-eu-ban-russian-crude-affects-oil-flows-2023-02-27/

Reuters. (2024, August 30). Russia payment hurdles with China partners intensified in August, sources say. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/russia-payment-hurdles-with-china-partners-intensified-august-sources-say-2024-08-30/

Reuters Staff. (2023, February 2). EU embargo, price cap target Russian oil products. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/eu-embargo-price-cap-target-russian-oil-products-2023-02-02/

Reuters Staff. (2025a, March 11). Crude shipments on Druzhba pipeline have resumed, Hungary says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/crude-shipments-druzhba-pipeline-suspended-after-drone-attack-hungary-says-2025-03-11/

Reuters Staff. (2025b, March 25). How Russian energy trade might change if sanctions are eased. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/how-russian-energy-trade-might-change-if-sanctions-are-eased-2025-03-25/

Russia | Economic Indicators, Historic Data & Forecasts | CEIC. (n.d.). Www.ceicdata.com. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/country/russia

Russia National Wealth Fund Assets. (2024). Tradingeconomics.com. https://tradingeconomics.com/russia/national-wealth-fund-assets

Russia suspends crude supplies to Poland via Druzhba pipeline: PKN. (2023). S&P Global Commodity Insights. https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/crude-oil/022723-russia-suspends-crude-supplies-to-poland-via-druzhba-pipeline-pkn

Russian Gas Unlikely to Return to Europe in Large Volumes. (2024, April 2). Fitch Ratings. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/corporate-finance/russian-gas-unlikely-to-return-to-europe-in-large-volumes-02-04-2025

Sharifli, Y. (2025, March 26). Power of Siberia 2: A Pipeline Between Ambition and Uncertainty. Trendsresearch.org. https://trendsresearch.org/insight/power-of-siberia-2-a-pipeline-between-ambition-and-uncertainty/

Statista. (2023). Russia: Oil & Gas Sector Share of GDP Quarterly 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1322102/gdp-share-oil-gas-sector-russia/

Sudan’s latest ceasefire fails to hold despite truce extension. (2023, May 31). Euronews; Euronews.com. https://www.euronews.com/2023/05/31/sudans-latest-ceasefire-fails-to-hold-despite-truce-extension

Szyszczak, E. (2025, February 19). Sanctions effectiveness: what lessons three years into the war on Ukraine? - Economics Observatory. Economics Observatory. https://www.economicsobservatory.com/sanctions-effectiveness-what-lessons-three-years-into-the-war-on-ukraine

Tan, F., & Verma, N. (2025, February 14). Latest US sanctions on Russia throw global oil trade into disarray. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/latest-us-sanctions-russia-throw-global-oil-trade-into-disarray-2025-02-14/

The Czech Republic no longer depends on Russian oil. (2025, April 18). OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2025-04-18/czech-republic-no-longer-depends-russian-oil

The International Working Group on Russian Sanctions. (2024, November 15). Stanford Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. https://fsi.stanford.edu/working-group-sanctions

The state of China–Russia cooperation over natural gas. (2023, February). International Institute for Strategic Studies. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2023/the-state-of-china-russia-cooperation-over-natural-gas/

Tracking the impacts of EU’s oil ban and oil price cap. (n.d.). Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. https://energyandcleanair.org/russia-sanction-tracker/

TRADING ECONOMICS | 20 Million Indicators for 196 Countries. (2025). Tradingeconomics.com. https://tradingeconomics.com/russia/national-wealth-fund-asset

Turkmenistan’s natural gas exports to China outearn Russia’s supplies. (2024, May 1). Eurasianet. https://eurasianet.org/turkmenistans-natural-gas-exports-to-china-outearn-russias-supplies

U.S. Sanctions Catch Up to Chinese Supplier Wison for Illicit Delivery of a Power Plant to Arctic LNG 2. (2025, January 13). High North News. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/us-sanctions-catch-chinese-supplier-wison-illicit-delivery-power-plant-arctic-lng-2

White House directs officials to draft proposal to lift US sanctions on Russia. (2025, March 3). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/03/trump-sanctions-russia

Yuan accounts for 99.6% of exchange forex trading on Moscow Exchange after sanctions, OTC volumes unchanged - CBR. (2024, July 10). Interfax.com. https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/104162/

Comments